Can we do any less? What 9/11 taught us about the importance of public safety radio

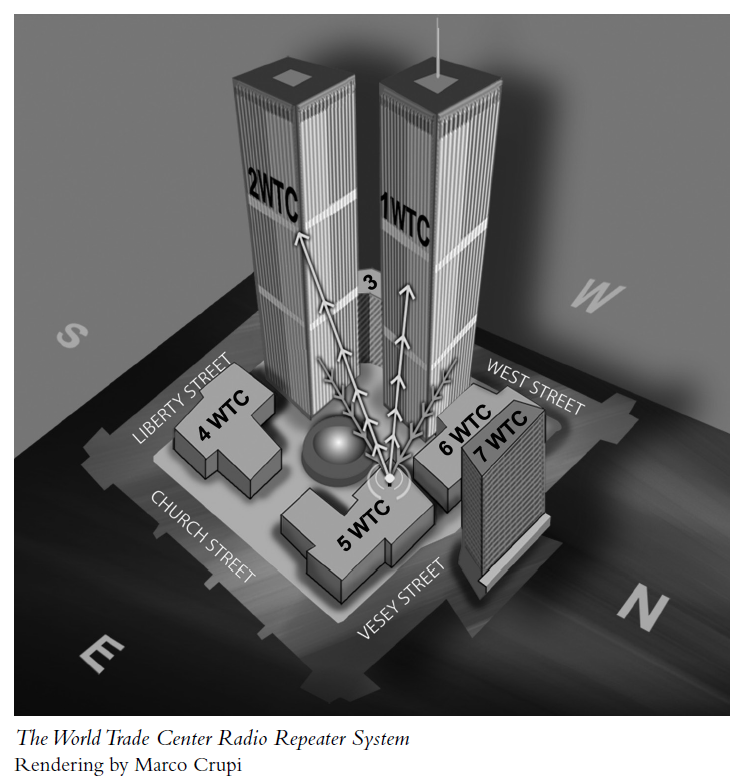

We’re only two days away from the 20th anniversary of 9/11. According to the 9/11 Commission Report, radio problems prevented many public safety personnel from hearing the eventual evacuation order. "The main problem, the FDNY says, was the damage done to infrastructure called repeaters, which made radio signals work at the Twin Towers. That left many commanders and firefighters unable to talk to each other. Firefighters in the stairwells couldn’t hear the evacuation order, and as a result, 343 died." Official 9/11 Commission Report findings on in-building radio coverage Radio coverage problems at the WTC were identified well before 2001. In the after-action studies of the 1993 WTC bombing, poor in-building radio coverage was identified as a critical factor, and a solution was deployed. However, the solution failed on 9/11. You can read the 9/11 Commission's report. Here are some excerpts: page 283-4 The FDNY’s radios performed poorly during the 1993 WTC bombing for two reasons. First, the radios signals often did not succeed in penetrating the numerous steel and concrete floors that separated companies attempting to communicate; and second, so many different companies were attempting to use the same point-to-point channel that communications became unintelligible. The Port Authority installed, at its own expense, a repeater system in 1994 to greatly enhance FDNY radio communications in the difficult high-rise environment of the Twin Towers. The Port Authority recommended leaving the repeater system on at all times. The FDNY requested, however, that the repeater be turned on only when it was actually needed because the channel could cause interference with other FDNY operations in Lower Manhattan. [This led to the introduction of the ARCS requirement in NYC. Management of BDA interference continues to be an issue today - see the link here on the SBC No Noise Task Force]. The repeater system was installed at the Port Authority police desk in 5 WTC, to be activated by members of the Port Authority police when the FDNY units responding to the WTC complex so requested. However, in the spring of 2000 the FDNY asked that an activation console for the repeater system be placed instead in the lobby fire safety desk of each of the towers, making FDNY personnel entirely responsible for its activation. The Port Authority complied. Pages 297-8 Page 323 The FDNY has worked hard in the past several years to address its radio deficiencies. To improve radio capability in high-rises, the FDNY has internally developed a “post radio” that is small enough for a battalion chief to carry to the upper floors and that greatly repeats and enhances radio signal strength. The story with respect to Port Authority police officers in the North Tower is less complicated; most of them lacked access to the radio channel on which the Port Authority police evacuation order was given. Since September 11, the Port Authority has worked hard to integrate the radio systems of their different commands. Problems at the Pentagon too Page 315 Several factors facilitated the response to this incident, and distinguish it from the far more difficult task in New York. There was a single incident, and it was not 1,000 feet above ground. The incident site was relatively easy to secure and contain, and there were no other buildings in the immediate area. As the “Arlington County: After-Action Report” notes, there were significant problems with both self-dispatching and communications: “Organizations, response units, and individuals proceeding on their own initiative directly to an incident site, without the knowledge and permission of the host jurisdiction and the Incident Commander, complicate the exercise of command, increase the risks faced by bonafide responders, and exacerbate the challenge of accountability.” With respect to communications, the report concludes: “Almost all aspects of communications continue to be problematic, from initial notification to tactical operations. Cellular telephones were of little value. . . . Radio channels were initially oversaturated. . . . Pagers seemed to be the most reliable means of notification when available and used, but most firefighters are not issued pagers.”

Page 397 Recommendation: Congress should support pending legislation which provides for the expedited and increased assignment of radio spectrum for public safety purposes. Furthermore, high-risk urban areas such as New York City and Washington, D.C., should establish signal corps units to ensure communications connectivity between and among civilian authorities, local first responders, and the National Guard. Federal funding of such units should be given high priority by Congress. [Note: In part, this resulted in the creation of FirstNet]

Since 9/11, we have seen many actions and initiatives to address the serious problem of public safety radio coverage gaps inside buildings, such as fire and building codes requiring coverage, improvements in the technology that makes this possible (BDAs, DAS, and other solutions), and the evolution to broadband coverage and interoperability as envisioned in FirstNet. But we are still experiencing growing pains. The codes and standards themselves are relatively new and immature. For example, fire sprinkler code has been around since 1896, while radio coverage codes began to appear in 2009. Problems include inconsistent code enforcement and interpretation, and the result of this includes wide variations in system cost and quality as well as an increase in system-disrupting interference. These issues are being addressed with urgency and significant effort in the Safer Buildings Coalition's No Noise Task Force [click to read]. The report also detailed the challenges of the commercial cellular network - in some cases failing due to massive congestion, but also failing due to a lack of in-building coverage and a lack of location accuracy. Conclusion In-building communications problems are not limited to massive high-rises like the WTC – in fact, there are millions of buildings in the US alone that need some form of wireless reinforcement. So how do we scale to such a massive requirement? How can we possibly get adequate coverage into every building that needs it? As the Commission Report details, there were about 150 agencies that responded to the WTC on 9/11. This included not just FDNY, but also NYPD, Port Authority Police, and many others. All public safety agencies must be able to communicate inside buildings. The public must also be able to communicate, and with the advent of FirstNet, both public safety and the public they protect have a mutual interest in reliable in-building coverage for commercial cellular networks. It will take more than a village to solve this - it will take an ordered ecosystem, a sense of urgency, and the will to execute. And with so much at stake ….. can we do less? |

“On Sept. 11, 2001, as firefighters rushed into the smoldering twin towers, their radios went dead."

“On Sept. 11, 2001, as firefighters rushed into the smoldering twin towers, their radios went dead."